The thirteenth episode of the Careful Thinking podcast features my conversation with Sarah Munawar. Sarah is a political science instructor at Columbia College in Vancouver, Canada, and she was recently a visiting professor at the Elizabeth Rockwell Centre on Ethics and Leadership at the Hobby School of Public affairs at the University of Houston in the United States. She earned her PhD in political science at the University of British Columbia in 2019, with a thesis entitled ‘In Hajar's Footsteps: a Decolonial and Islamic Theory of Care’, which will form the basis of a forthcoming book.

Sarah describes herself as a neurodiverse Muslim mother and political theorist, her research articulating a vision of health equity, disability justice and care ethics that is intersectional, Islamic, and decolonial, while also centring the epistemic authority of disabled Muslims as knowers of Islam, Muslim practices of care, and care-based modes of knowing Islam. Her publications include the book chapter ‘In the Belly of the Whale: Theorizing Disability through a Decolonial and Islamic Ethic of Care’, which was published in 2022, in the collection Care Ethics, Religion, and Spiritual Traditions; the journal article ‘The Breathwork of Ar-Rahman, An Islamic Ethic of Reproductive Care’, also from 2022; and the book chapter ‘ “Be and it is!” : Muslim Cosmologies of Care, Desire, and the Reproduction of Life’, which will appear later this year.

A number of earlier episodes of the podcast have discussed the influence of religious belief on ideas about care, as well as the connections and tensions between faith and feminism. However, those conversations (for example, with Xavier Symons in Episode 2, Ruth Groenhout in Episode 5, Maurice Hamington in Episode 6, and Carlo Leget in Episode 8) have focussed mainly on the Christian tradition. So in this episode, I was really interested to explore with Sarah her project of developing a specifically Islamic ethic of care, one that's also feminist in orientation. As someone with a very limited knowledge of Islam, I’ve learned a great deal from reading Sarah’s published work, and as a result of my conversation with her. I’m intrigued by the ways in which she draws on Qur’anic stories, and in particular narratives of strong women, such as Hajar and Maryam (Hagar and Mary in Jewish/Christian scriptures), as ways of understanding her own experience, and as resources for developing a Muslim feminist theory of care.

My conversation with Sarah recalled several earlier episodes of the podcast. For example, Sarah’s advocacy for her father’s continuing personhood, when in a coma, in the face of medical denials, reminded me of my discussion with Xavier Symons in Episode 2, about the inalienable personal dignity and worth of people suffering from dementia: see also this post. However, perhaps the most striking parallels were with my conversation with Aaron Jackson in the most recent episode of the podcast. Like Aaron, Sarah’s theorising about care has arisen from often traumatic personal experiences, both of caregiving and of receiving care. Just as Aaron’s academic writing draws on his experience of caring for his disabled son, as well as his own serious illness, so Sarah’s work has grown out of her family’s experience of caring for her father in his long-term illness, and her personal experience of giving birth during the Covid-19 pandemic. Aaron and Sarah are both severely critical of certain aspects of medical discourse and practice, and both advocate for a radically different way of viewing the personhood of people with disabilities. As was true in Aaron’s case, I’m extremely grateful to Sarah for sharing her personal experiences so openly on the podcast, and for reflecting on them so honestly and thoughtfully.

Sarah MunawarWe began our conversation by exploring the roots of Sarah’s thinking about care in her family’s experience, over the past decade, of caring for her father, following his stroke and confinement in an intensive care unit. Sarah described what she regards as the medical ableism and racism that she and her family have experienced, but she was also critical of some ways in which their experience has been viewed within the Muslim community. In particular, she criticised the tendency to deny her father’s continuing personhood and to construe her family’s, and in particular her mother’s situation as tragic. Against this background, Sarah and her family have drawn on their Islamic beliefs, and in particular on stories from the Qur’an, as resources to understand and support their caregiving. However, as well as her religious faith, Sarah’s view of her father’s experience and of medical responses is also set within a disability justice framework. At a number of points in our conversation, Sarah referred to Eva Kittay’s ground-breaking book, Love’s Labor, which has clearly been a major influence on her thinking about disability, dependency and care, though we also discussed Sarah’s ambivalence towards aspects of feminist care theory and her quest for a decolonial ethics of care. In the second half of the episode, we talked about Sarah’s traumatic experience of becoming a mother during the pandemic, which prompted her drive to develop a Muslim feminist ethic of reproductive care, an ethic which in Sarah’s view also has global political and ecological dimensions. Going forward, Sarah is keen to develop this ecological emphasis further, focusing on the importance of the concept of place for care, in her future research and writing.

Here are a few quotes by Sarah from the episode:

So in classrooms, we would be talking about moral personhood, reading Rawls and defining who is a person, what is a political subject, and...which lives are seen as worthy to us. That was the conceptual language in class. And then in the hospital waiting rooms, we would be having very intense conversations weekly, we call it ‘pulling the plug’ conversations, where... doctors would signal to our family that your father's life is no longer valuable or meaningful, if he ever returns from the state of a coma after his stroke. They were using quite a bit of ableist language that I don't really repeat anymore, but it was just...he is just no longer of value or worth to you, to this world. The language was of burdens, that...someone with such severe disability after an illness or injury, their contributions to your family or to society, or the way that they will inhabit fatherhood, it will only be a burden, and it's only tragic, it's a horrible thing that's happened. And I really felt that way of thinking was really harmful.

...

Caregiving is not a bad thing...It's a responsibility that all Muslims hold in our families, in our communities, in our worlds. To care and be entangled in dependency, care, it's not a burden, nor is it something we should shame people for. It's a natural part of human experience. But...even just saying that and thinking that and fighting for our father's worth and humanity, in the hospital space, we were met with a lot of hostility.

...

So when he was in the coma and when he was recovering from his stroke, initially doctors were obsessed with the language of eye tracking and movements. All parts of his entire identity were broken down into symptoms and changes in symptoms and medical language. So I found that very fragmentative, or just like a splintering of his entire identity and his relationships with the world. And we would contrast that with...quite spiritual experiences we've all had of dreams of our father, encounters with him as he's become disabled. We've all come closer...our family relationship has only grown and I would say nourished in incredible ways. But none of that is continuous with the way he's been typecast as a patient with these symptoms, with these pathologies, with this certain worth of life in medical world. So it's just been hard to reconcile how we've experienced disability and his change of being in the world and how we relate versus doctors’ typecasting.

...

So I would say that medical ableism and medical racism targets our family's relationships and our place in the world, and families like mine all over the world, who are in dependency care situations, targets disabled Muslims...We're all vulnerable, we're all interdependent, and we're going to be disabled at some point in our life and need each other again. So...I found that our transformation into a different care web was seen as this great, tragic break from what is normal for so many things, like institutions, families, society, and for us, it's the best kind of normal we've ever known. So I can't reconcile these two worlds.

...

For my family, selfhood is relational. In care ethics, we always theorize personhood as relational, but also within indigenous feminist frameworks, or spiritual or faith-based frameworks, the self is relational, it's entangled. Who we are is tied to who others are, our needs, our rights, our responsibilities...But in state institutions, you're only allowed to relate to each other as individuals with different sets of rights. So...I can theorise all these lovely things about relational autonomy and how we have to show up for each other as relational selves. But at the end of the day, I still can't convince ICU directors and...doctors of the value and worth of these relationships for meeting access, needs and rights. So it's hard...There's a big divide, and I think the value of theorising Islamic moral vocabularies of the self as relational, the value is that you build that language. You find how it has parallels in the rights-based language world, and then you try to keep articulating the value of staying together as a unit. It could be chosen kin, it could be family. Just staying together as your relational unit in hospital space, like, that's my goal, to bridge it, to find, to help families like mine find the words to say, we are attached to this person, this person needs us.

...

‘The breathwork of Ar-Rahman’ just means God is, or Allah is, caring, compassionate, He is ever loving. He's a source of compassion and mercy for us. And my family has been positioned in a very difficult place in this world. And the only respite and coolness and nourishment that we find is in that breathwork of God's care, in our life and wherever we find it... So it's just in those stories, I find a lot of resonance again and a lot of assurance that... Allah is a witness. He is watching us. He is pouring and nurturing our life. He is supporting us and making it possible for us to take care for our kid despite the conditions of our existence. It’s just the presencing of Allah's witness...He sees and He witnesses and He provides, even when people have refused to care for you or the world has, or even when it might feel like the world has spit you out.

...

I have a heightened sense of ecology growing in my writing. So I'm hoping and praying that in my upcoming book project, I'm centring a lot of more land relationships as well. So much of my theorising has been family relationships, community relationships of care, mothering, or caring for elders or parents. But a big part of that has become land as well. So I think so many Muslim communities live in a context of exile and displacement, where our relationships to the land have been cut off as a way to erase, assimilate, or destroy our cultures and our sense of identity and our sovereignties. So I think when we're theorising Islamic care ethics, there has to be a conversation on land. And I've learned that also by friendships and conversations and scholarship by indigenous feminists in Canada. So I'm just grateful for that awareness of land and theorising that into care ethics through those friendships. So more than land, I try to theorise place... a place for care, so being able to find food for your child, being able to take your child to school safely, being able to have a place in this world where you and your family or your loved ones or your kin are accounted for, taken care of, and you're able to fulfil those moral responsibilities that you feel for yourself.

You can listen to the whole episode here, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can download a transcript of the episode here:

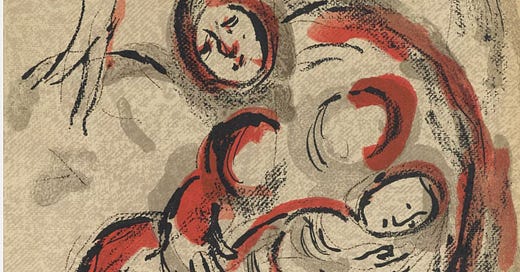

The header image is ‘Hagar in the Desert’ by Marc Chagall (1960)

Good to know, Elissa. Thanks for the feedback - much appreciated.

Really enjoyed this. Thank you!