Man up or open up?

Young men, masculinity and mental health

Earlier this month I was a guest speaker at a conference on mental health organised by the Sixth Form Colleges Association. (In the UK, ‘sixth form’ denotes the final two years of secondary education, in which 16-18-year-olds study for Advanced Level qualifications.)

My presentation was entitled ‘Young men, masculinity and mental health’, and it drew on research that I’ve undertaken over the past fifteen years or so, with colleagues at The Open University, exploring the links between ideas and expectations around masculine identity and young men’s mental and emotional health and wellbeing.

Although young women between the ages of 16 and 24 are three times more likely to experience mental health issues than young men of the same age, we know that young men are more likely to become dependent on drugs or alcohol and to die by suicide than their female counterparts. What’s more, mental health issues such as depression are often more difficult to diagnose in young men, one reason being that they are less inclined to share their feelings. And statistics show that young men are also much less likely to seek professional help.

In my talk, I discussed two major research studies in which I’ve participated. Between 2013 and 2015, I led a nationwide study, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council, with the title Beyond male role models: gender identities and practices in work with young men, in which our team at The Open University collaborated with the UK-wide charity Action for Children, as well as the London-based organisation Working with Men (now Future Men), to explore the role of gender in the lives of young men in contact with care services. We carried out interviews with young men in London, North Wales, South-West England, and the West of Scotland, and you can watch the short film we made at some of those sites here.

Then, in 2016-17, I was asked to lead the UK strand of a three-country study – in the United States, Mexico and the UK – exploring young men’s attitudes, behaviours, and understandings of manhood. The Man Box project was overseen by the international gender equality organisation Promundo (now Equimundo) and funded by Axe-Unilever. Our study in the UK, which had the title Young men, masculinity and wellbeing, involved organising focus groups with mainly socially disadvantaged young men in London and the north of England, talking with them about friendship, family relationships, and their views on gender identity and gender relations.

We’ve published the findings from these research projects in reports, journal articles, and book chapters, and we’ve also presented our findings to parliamentarians, civil servants and care professionals. The research has also led to a fair amount of media attention. For example, last year, BBC Radio 4 broadcast the series About the Boys, talking to young men about their lives, and to researchers and professionals working with boys. I was one of the people interviewed for that series, and my research was featured in the first programme.

In both of our research studies, we found evidence that, despite the significant changes that have taken place in gender roles and relationships over the past few decades, some fairly conventional expectations about what it means to be a man persist – and continue to shape the lives of today’s boys and young men. However, we noted that the impact of these gender norms varies enormously across social and economic groups, with some groups of young men being much more affected than others, and different groups being affected in different ways.

Perhaps surprisingly, despite the assumption that all young people today are exposed to more or less the same influences via the media and online, we found significant geographical and cultural differences in ideas about gender among young men. And while most young men in our studies expressed broad support for gender equality, we came across pockets of resentment, resistance and even anger, often directed towards women and girls, and a sense among some groups of young men that the pendulum of equality had swung too far, with men now the stigmatised and disadvantaged gender.

So how do these ideas and expectations around being a man affect young men’s mental and emotional wellbeing? Firstly, we found that many young men feel a pressure to conform to those expectations, whether it’s about achieving economic status, or success in relationships and sexual experience, or simply projecting the right kind of body image. And these pressures can create a degree of stress and anxiety for young men. As one of the young men we spoke to said, ‘there is a pressure everywhere to tell you what kind of man you should be’, while another claimed that ‘you have to be a man who’s got a nice house, a nice car, a family with kids, a good job’.

Importantly, the young men we spoke to agreed with the notion that men find it more difficult than women to express their feelings, and many said that they would find other ways to deal with problems rather than asking for help – whether from those close to them or from professionals. One young man suggested that ‘men, we just deal with it differently…we’ve got other channels for expressing our feelings,’ while another said that he and his friends simply ‘bottle it up and get on with it…work it out…go to the gym…just put the kettle on.’ And among some groups of young men, admitting to mental health issues was seen as ‘weak’ and ‘unmanly’. As one focus group participant said: ‘If anyone says they have depression, I think there’s weakness in them….it’s an excuse.’ We also found evidence that, for some young men, these defensive strategies can be self-destructive, involving abuse of alcohol or drugs, or destructive towards others, channelling difficult emotions into violence.

However, some of the participants in our studies were more reflective about the negative influence of these gender norms. As one young man said of his teenage years: ‘I hung out with very laddy mates, and we’d just talk about sex and drink and stuff...always boasting and never talking about our vulnerabilities...it would always be about how amazing we are, but never about how we’re really sad and lonely or about how we’re upset or worried about our futures or anything like that’. Another participant, looking back on a difficult time in his life, said: ‘I disconnected myself from other people, because I thought that was the manly thing to do.’

If all of this paints a fairly gloomy picture, then there were also some hopeful signs emerging from our research. As already mentioned, these negative masculine stereotypes don’t affect all groups of young men equally. And there were signs of attitudes changing. Other researchers have written about the recent emergence, among some groups of young men, of a ‘softer’, more expressive masculinity – one that is more in touch with feelings, more in tune with changing gender roles, and more respectful to girls and women. The fact that some of the young men we spoke to were able to articulate thoughtful responses to our questions was itself a positive sign.

What’s more, it’s certainly true – as we and other researchers have found – that when you talk with boys and young men individually, away from the pressure of the peer group, you often get a more nuanced picture than when raising these topics in all-male focus groups, where the pressure to competitively perform masculinity can inhibit honesty and openness. And in some of our individual interviews, we found an encouraging proportion of young men, even those who had experienced problematic family relationships themselves, expressing an aspiration to be responsible, involved fathers, and viewing participation in caregiving as central to their image of a ‘good’ man.

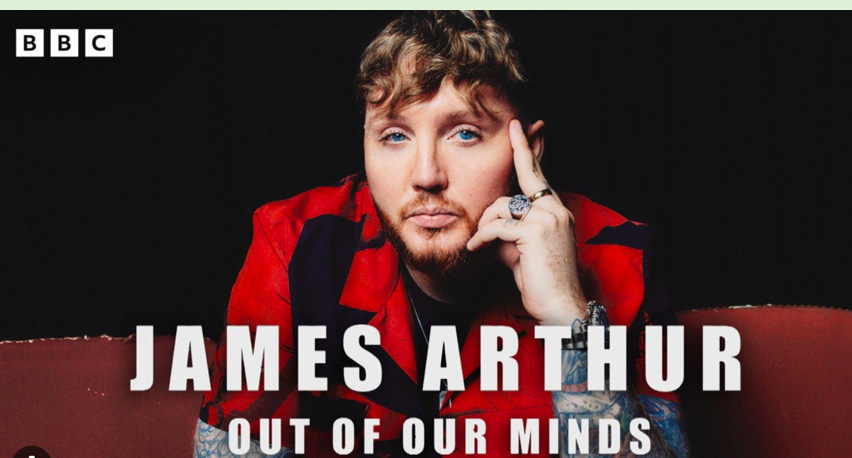

Towards the end of my conference presentation, I spoke about the BBC/Open University co-produced documentary James Arthur – Out of Our Minds, which was first broadcast in 2022, and for which I was the academic consultant. The programme follows the singer and X-Factor winner back to his hometown of Middlesbrough, as he attempts to trace the roots of his problems with anxiety and depression. Here we see a young man, from a tough, working-class background in the north-east of England, on a journey to becoming more open, honest and reflective about the mental health issues he has faced, and coming to a realisation that the ideas about being a man that he grew up with were in part responsible for some of those problems. And there are some particularly affecting scenes in the film of James talking with other young men from his hometown about their own struggles with mental health, scenes in which we see young men not afraid to show their care for each other, and to acknowledge their own vulnerability.

In the Q&A session that followed my conference talk, someone asked how we - as educators, parents, mentors - can encourage young men to embrace a more expressive - and caring - masculinity. My response was that we need to show young men that doing so not only benefits the other people (and especially the girls and women) in their lives, but that this kind of positive masculinity is also good for young men themselves, leading to happier, healthier lives.

To accompany the James Arthur documentary, our team at The Open University developed the animation Man Up or Open Up? , exploring the question of why men find it so difficult to talk about their mental health. The film also reflects my more recent work, exploring initiatives that are finding creative and imaginative ways to engage men - including young men - in talking about mental health (see these posts). Although the video is about men in general, rather than young men specifically, I think it captures quite well some of the key points I was trying to get across in my conference presentation:

Header image via Shutterstock.

such important work!