The transformative power of care - with Elissa Strauss

Episode 16 of Careful Thinking

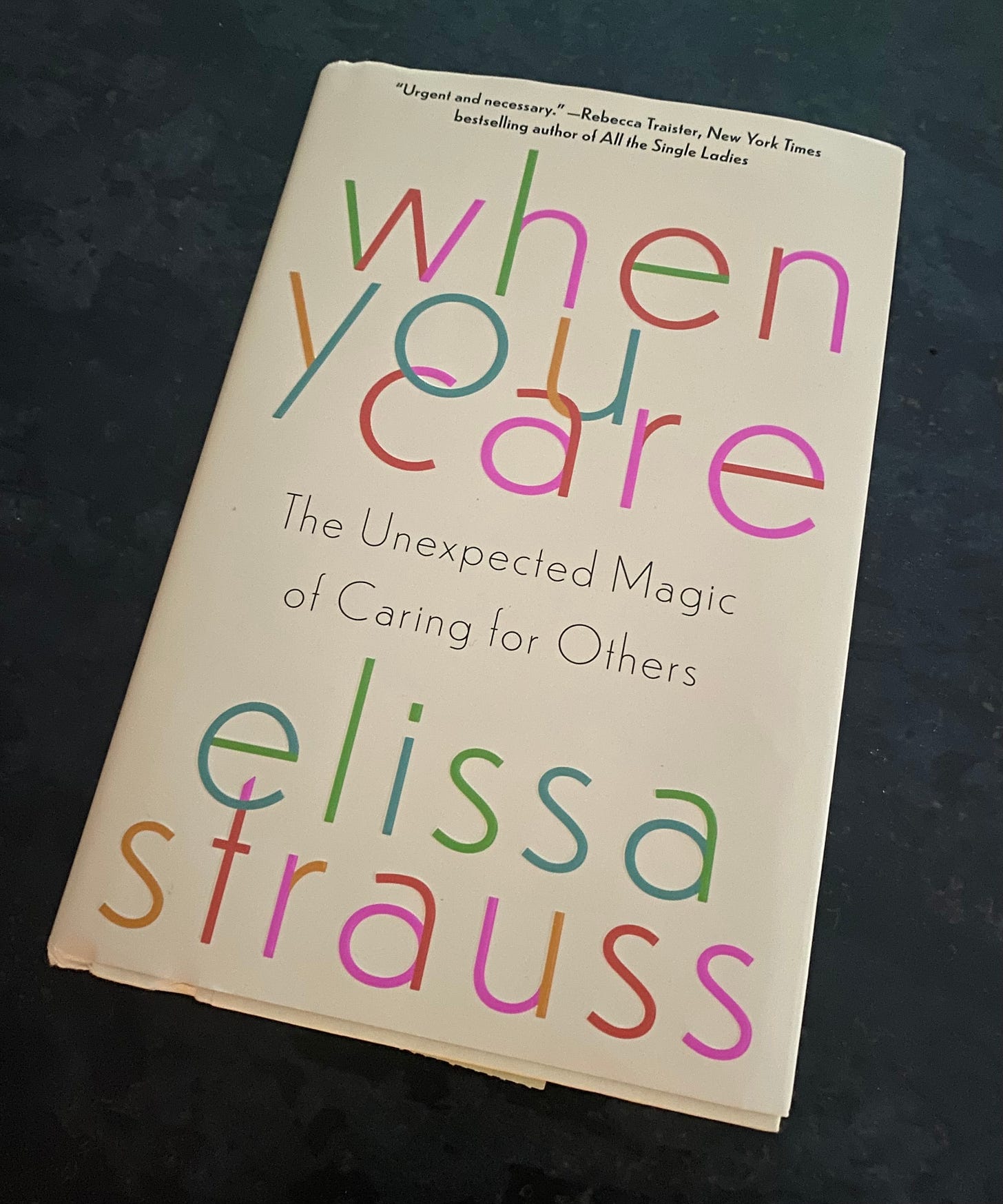

For the sixteenth episode of the Careful Thinking podcast, I was delighted to welcome as my guest Elissa Strauss, the author of When You Care: The Unexpected Magic of Caring for Others, which was published earlier this year to widespread acclaim. Reviewers have described the book as ‘brilliantly argued and timely’, ‘urgent and necessary’, and ‘destined to be a modern classic’. According to The Nation, ‘Strauss...writes movingly about the value of intimate care – not only its economic value to society but also its psychological, physical, and even spiritual value for those who perform it.’

I first heard about the book via Substack, and everything I heard made me keen to read it. However, as the book is yet to be published here in the UK, it took me a while before I could get hold of a copy. But it was certainly worth waiting for. I think it's a timely and important book, one which provides insights into aspects of care which haven't received much attention to date, and also one which performs the valuable service of bringing urgent debates about care to a wider public audience.

Based in Oakland, California, Elissa is a journalist, essayist and opinion writer who has been writing about the culture and politics of care for fifteen years. Her work has appeared in publications such as The New York Times and The Atlantic, and she's been a contributing writer for CNN and Slate, where her articles have focused on feminism and motherhood. In the course of our conversation on the podcast, Elissa mentioned an article she was writing for The Atlantic about care ethics, which has since been published as ‘The branch of philosophy all parents should know’ (see this recent post). In addition to her work as a writer, Elissa is also an artistic director of LABA, a Laboratory for Jewish Culture.

Elissa Strauss

Our conversation on the podcast began by exploring the roots of Elissa’s career as a writer, before focusing on her reasons for writing When You Care, and its origins in both her longstanding feminist and political concerns about care and in her personal experience of caregiving as a parent. Elissa talked about how motherhood had been presented to her as either a fairytale or a nightmare, but how by contrast she found it to be a personally transformative experience, one through which meaning could be found via ‘generative friction’. We then discussed the value of care to society and how this is often overlooked in political and economic discourse. Turning to the ways in which feminist thinkers have written (or failed to write) about care, Elissa reported on her extensive research into an alternative feminist history of ‘care feminism’. For Elissa, men’s equal participation in caregiving is vital to developing a culture of care, and we talked about the potential of care to change men and masculinity. One of the main messages of Elissa’s book is the transformative power of care in the lives of those who care, and next we turned to research on the physical and psychological benefits of caregiving.

The book as a whole is informed by the ideas of feminist care ethics and we spent some time discussing Elissa’s life-changing discovery of this branch of philosophy. The final, and in my view one of the most valuable chapters of the book, is the one on care and spirituality, and Elissa talked about the ways in which becoming a parent reinvigorated her own participation in Jewish religious practice, while at the same time highlighting the absence of a focus on everyday, interpersonal care in traditional religious discourse. Finally, with a presidential election imminent in the United States, and a new government recently elected here in the UK, we talked about what those with political power can do to support the development of a culture of care.

Since my own academic research has focused mainly on men’s participation in care, I was pleased to see that Elissa devotes a whole chapter of her book to the subject. Not only that, but the chapter begins by describing the work of the international gender equality organisation, Promundo, with men in Rwanda. I’ve worked closely in the past with Promundo, which recently changed its name to Equimundo. With my co-researchers Sandy Ruxton (now the co-host of the excellent Now and Men podcast) and David Bartlett (now a senior research fellow with Equimundo), I carried out a study of the impact of social expectations around masculinity on the lives of young men in Britain, which formed part of a three-country project in the UK, Mexico and the US, which was coordinated by Promundo. The findings of our study echoed Elissa’s perception that, despite continuing pressures to conform to rigid cultural constructs of masculinity, younger men today are generally more open to taking on caregiving than their older counterparts. My discussion of these issues with Elissa recalled previous episodes of the podcast, specifically Episode 6 with Maurice Hamington and Episode 12 with Aaron Jackson, which also explored men, masculinities, fatherhood, and care.

As I mentioned in the podcast, Elissa’s chapter on care and spirituality had a particular personal resonance for me. At the same time, I had some initial reservations about her claim that mainstream religious traditions had ignored care, and that women had traditionally been excluded from ‘the discipline and study and solitude and prayer that generally only men do, all activities that lead to power and authority’. In the tradition I know best, there have been plenty of women who got to study and pray and have influence: I’m thinking about women like Hildegard of Bingen, Catherine of Siena and Teresa of Avila, and in more recent times, philosophers like Edith Stein and activists like Dorothy Day. Add to that the fact that, until the modern era, most of the caregiving in society was actually done by religious institutions - and to be fair, in the book Elissa does acknowledge that ‘monks and nuns, as part of their spiritual practice, cared for the needy’. But on reflection, I realised that none of the prominent holy women I mentioned (with the possible exception of Dorothy Day) actually had experience of, or wrote about, intimate care for loved ones within the family, and neither was this the concern of those charitable religious institutions. So I came to the conclusion that, although Elissa had possibly overstated the case for effect, her basic point, about the relative absence of a concern with everyday, interpersonal care in mainstream religious discourse, was probably a valid one.

Elissa recently published an article about the biblical story of Abraham and Isaac, discussing the message it conveys about parenting and the value of fatherhood, and she also mentioned on the podcast that her next project will be an exploration of masculinity, particularly in the Jewish tradition, beginning with a focus on the King David story. I thought there were some interesting parallels here with my conversation, in Episode 13 of the podcast, with the Muslim scholar Sarah Munawar, who uses stories from Islamic scriptures in her work to illuminate contemporary issues around care. Interestingly, Sarah also focuses in her writing on the Abraham / Ibrahim story, or rather on the story of his wife Hagar / Hajar. It seems there’s no escape from this biblical story on the podcast: in Episode 3, Nigel Rapport drew on Emmanuel Levinas’ use of the story of Abraham’s encounter with God to illustrate his thesis about the unknowability of the ‘other’, and it also gave Nigel the title of his recent book about Levinas and anthropology (see this post).

There’s plenty more in When You Care that we didn’t have time to discuss on the podcast. I particularly enjoyed the chapter on evolutionary theory, in which Elissa makes the revisionist argument that, rather than being wired for competition and survival of the fittest, we may in fact be hard-wired for care, and which has a fascinating section headed ‘Charles Darwin was a good dad’. Who knew?

Here are a few quotations by Elissa from the podcast episode:

I know...many other people discover this as well, but it was genuinely novel to me...that care turned out to be one of the most intellectually, philosophically, psychologically, even spiritually challenging and enriching things I could do. And it took a couple of years, it took for my older son to start really talking, and then...because I'm such a language person, I guess the real self really revealed itself to me with language...And it's one of these things that's so obvious. And yet when you really encounter an ‘other’, when you're really forced, which care does, to be in the presence of just an entirely different human, it can be a radical experience. And it was for me.

...

Care, particularly motherhood, but I think care more broadly...had either been presented to me as a fairy tale or a nightmare. And the fairy tale is a very sanitised, sentimentalised version of care that we've got from a lot of world faith traditions...and it was a sweet, protected space away from the stresses and troubles of real life outside the home, away from power, away from politics, away from money...And then we started getting a correction to that, a necessary correction, and this kind of nightmare version of care...where women were saying, ‘Hey, wait a minute, this is hard, this is...challenging’...and voicing the darker, harder parts of care. Some of them made the connection between the struggles they were having and the lack of care infrastructure, the lack of support for caregivers. But others also just wanted to voice that this isn't the sweet, harmonious thing, actually, to care for another person is really difficult. And...I'm glad that those voices were out there, and I'm glad that we had a chance to talk about those darker sides...And so I felt like...I'm stuck in between these two, the fairy tale and the nightmare. And I actually think both are missing the meaning piece. And I think we all know that real meaning doesn't come from pure joy or pure misery. Meaning comes from friction and conflict. But it could be generative friction and conflict. And that was what I was so interested in.

...

We...need...to break what I call in the book ‘glass doors’. We need to break this idea that our care selves should be kept separate from our otherwise public selves, that we should let those care selves out and be part of who we are in our friendships, in our professional lives, that we get so much from care, we are so enriched by care. Instead of trying to keep those separate...we should feel free and be proud to merge those identities. And at the same time, we also need the public...to enter the home and understand that caregivers, mothers, fathers, and everyone else need support from the public in their care space, in the space where they are tending to others who are dependent on them. And right now, caregivers and parents feel so isolated and feel so alone, and it's such an economic burden to care for so many people. And I think that's because we have these doors up. We have these Victorian notions that the home is a private space and everything else is the public space, and they should not mix. And as one woman I'd call a care feminist, writing a hundred years ago, trying to agitate for a woman to get the right to vote in United States, said, ‘Home is a woman's place, but home is everywhere’...And for me, what I really take from that, is that when we get out in the world and we try to make it more accommodating for people who care, and we have more curiosity about the experience of people who care, and when we see all that infrastructure that happens outside of our homes as supporting the caregivers, we win.

....

Men today are both emotionally connected to their kids and doing the practical labour of care...I know there's a lot of conversation about the domestic labour burden and all the stress that puts on women, and I think that's very real and important, but I ... don't think we're going to actually have the kind of conversation that we should have and need to have for real change, if we don't also acknowledge that men are doing so much more care, and to work a little harder to understand why they're not doing equal amounts to women. Because I think those reasons, when we dig in, are both psychological - they were not raised as caregivers - and also structural...I think we still have to see the fight for dads getting more involved with care, with the fight for broadening our notion of what it is to be a man. Not dismissing those kind of traditional masculine virtues or being kind of the strong, stoic one, or being the responsible one, or being the physically playful one, but just expanding them...And...we've seen that care...can really make a space for this for men.

...

This book wouldn't exist without care ethics. The care ethics chapter may come second to last in the book, but spiritually, intellectually, narratively, was the place I started. It was the first body of writing that changed the way I saw everything...a before-and-after moment in my life...And I had never, ever in my life seen anyone treat care as worthy of deep curiosity like the care ethicists. And...layered on top of that, that care could ...be part of something we call the good life.

...

I say I believe in God, but don't ask me to...define exactly what that means, and if I even try to, the whole thing turns to dust and falls on the ground. But I nevertheless find the relationship with this thing I call ‘God’, but can't define, as fruitful in my life...For me, one of the realest ways that care led me to a different kind of spiritual experience was my relationship with time. And time is so strange when you care. It goes all too fast and all too slow, all at the wrong moments. The kids grow and grow and grow, and their little chubby cheeks melt away. And add to that the reality that I created these two somehow unique individuals, and there's humans that exist in the world, and where do they come from? So between the mixture of the miracle of their existence, combined with the fragility of their existence, combined with the reality of time passing, brought me so much deeper into my practice as an observer of the Jewish tradition, and using Jewish tools to help order this crazy thing that is time. So I became, for the first time in my life, a deeper observer of the weekly Sabbath. And I have to say that that ancient technology of the Sabbath really helps me find a deeper, richer experience of care with my kids, because I feel like there's this...standing moment every week where we kind of reconnect and re-attune. So...it's just one example of the way my care experience and faith experience have been so tangled. And I just want to hear so many more people talk about that, because I know it's real for many.

You can listen to the whole episode here, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can download a transcript of the episode here:

The header image is the painting ‘Mother and Child’ (1959) by Miriam Schapiro.

Footnote: Episode 16 is the first anniversary episode of the Careful Thinking podcast, which launched in November 2023. I’ll be reflecting on a year of podcasting about care in a forthcoming post.