When I looked back on the first year of the Careful Thinking podcast in a recent post, I expressed surprise that so many of my guests had mentioned religious faith as an influence on their thinking about care. For this post, it being the season of religious festivals, I thought I would collect together everything my care theorist guests have had to say on the relationship between faith and care. (The quotations below are from guests who explicitly mentioned religion or spirituality on the podcast. Other guests may have had strong opinions or interesting things to say on the subject, but it didn’t come up in the course of our conversations.)

A number of my podcast guests said it was their religious faith and studies in theology that had led directly to an interest in care ethics and care theory. In Episode 8, Carlo Leget explained that ‘coming from a Catholic tradition and being interested in...spirituality and transcendence’ prompted his decision to study theology, which he described as ‘a wonderful intellectual adventure, and at the same time, a little bit moving away from contemporary society.’ However, it was theology that also ‘brought me to studying life and death, and the relation between life and death in contemporary culture...which in turn meant that I started to do empirical research in two nursing homes’, this being ‘the first time I was confronted with people dying, with people suffering, with healthcare issues.’ At the time, Carlo still saw himself primarily as a ‘moral theologian’, but ‘I more and more discovered my fascination with ethics’, and specifically the ethics of care.

Carlo Leget Inge van Nistelrooij Xavier SymonsIn Episode 17, Carlo’s colleague Inge van Nistelrooij described how she ‘started studying theology because I thought I would be a spiritual counsellor in hospitals’. But before long Inge became ‘interested in ethics and in the way that people live together and develop their ethic’, though by now she was less focused on being ‘a moralising teacher in ethics’ than on ‘searching and researching how culture and society and also personal human lives lead one to value certain things or to create norms in certain ways.’

Both Inge and Xavier Symons, my guest for Episode 2, described being inspired by the examples of caregiving they had witnessed in religious communities. Xavier mentioned ‘the example of nuns in the aged care homes that I volunteered in as a young adult’, and ‘seeing the dedication...and that legacy of service that these nuns had’, which reflected ‘the...profound emphasis on the importance of care that's part of the spirituality of these religious orders.’ Xavier described this as ‘a very formative experience and something that really brought home to me how this...something that's an essential need of human beings, to be cared for by others, and that as a society we don't lose sight of that.’ In a similar way, Inge acknowledged that ‘in the Netherlands...it was primarily the religious congregations that established caring institutions’. As she noted, ‘hospitals, elderly care institutions, social welfare institutions, and of course also educational institutions, were really set up by nobody else but the religious congregations’.

Inge’s early exposure to religious teaching provided the foundation for her own beliefs about care: ‘In Christianity, one key idea is that of mercy, and of course, in the Catholic Church, traditionally, there are some virtues and works of mercy that you can do or should do...for your neighbours.’ These include ‘visiting the sick, going to the people who are in prison, giving water to those who are thirsty, and food to those who are hungry, burying the dead’. And Inge noted that, although she had now ‘grown away from the Church’, she continues to be influenced by ‘this basic idea of...how should you live together as a society, in order for life to be good for all who are members of that society, and also to be responsive to appeals that people do to you.’

In a similar way, Xavier described how the Catholic social teaching which he absorbed at a young age had been central to his ethical formation: ‘I grew up in a family that has...a strong anchoring in the Christian social democratic tradition...and I think, to some extent...that also informed my concern for questions of social justice.’ Xavier clarified that ‘my tradition is…specifically coming out of...Catholic social thought and principles like solidarity, subsidiarity, preferential option for the poor, principles of the dignity of every human life, and…concern for the common good,’ noting that ‘these are principles that I think were instilled in me from a young age’ and which ‘made...working in ethics a natural progression...given that ethical formation I'd received as a kid and then throughout my university years.’

In Episode 5, the late Ruth Groenhout described how her grounding in theology had led naturally to a concern with care, recalling how at an early stage in her academic career she had written an article on ‘theology in an ethics of care’, which was informed by ‘quite a bit of Jewish thought’, though she added that ‘there's also a long history of Christian theology making love the centre of things...so when you move into care, there's a sort of natural connection between care and love.’ And Ruth gave a specific example of how the Christian emphasis on forgiveness might inform an ethic of care, showing ‘how important for relationships of love or care forgiveness is on both ends...that I forgive you, you forgive me, and we each actually learn to forgive ourselves...so I think that comes out of the Christian tradition and I do think it's very important.’

Both Ruth and Xavier spoke about specific religious thinkers who had informed their thinking about care. For Ruth, a key influence was St. Augustine: ‘I think of certain philosophers as people I can't walk away from...and Augustine definitely falls in that category for me, partly because I do come out of the Reformed Calvinist tradition, and Augustine is central for that’. Augustine was important for Ruth because ‘he really does think that God truly is love: we are made in God's image, and so we are created to love, which...makes love or care an absolutely central part of what you think about.’

For Xavier, it was Christian personalism that was the main philosophical influence, informing his belief that the dignity of the individual is fundamental to care: ‘The basic commitment of every form of personalism...is that persons are morally special and existentially special in the universe...that there's something wonderful and magnificent about being a unique and unrepeatable individual...that's an idea that comes through in the work of John Paul II, Karol Wojtyła.’ And Xavier cited Love and Responsibility, ‘where Wojtyła notes that the human being is a single, unique and unrepeatable individual...someone thought of and chosen from eternity, someone called and identified by name...focusing on this idea from Scripture, that God has called each individual by name, that He is with us.’ As a consequence of this fundamental belief, Xavier added, ‘there's a sense in which personalists are focused on ensuring that society's moral and social norms reflect a recognition that every human person has an inherent and inalienable dignity.’

Ruth Groenhout Maurice Hamington

Perhaps surprisingly, for one or two of my podcast guests, their theological studies had led not only to care ethics, but also to feminism. In Episode 6, Maurice Hamington recalled that when he was studying for a Master’s degree in religious studies, ‘my teachers and mentors there were very pro-feminist Catholics, and I got exposure to all kinds of feminist ideas.’ Maurice went on to study for a PhD in religious studies, ‘and while I was there, I took a graduate course in…women's studies and theory.’ In a similar way, Inge recalled that, when she was studying theology, ‘in every course…feminist texts were part of that curriculum’, while ‘a separate course...introduced me to feminist theology’, opening her eyes to ‘ecofeminism and...the Global South’, while ‘also I learned a lot about poverty and social economic low status, thanks to feminist theology.’

However, it was feminism that also influenced Inge’s eventual move away from the Church. As she put it, ‘studying theology...made me aware of the specific position that I have as a woman in the Roman Catholic Church, something I became more aware of even later on when the Church made several decisions which were not so much in favour of women in the Church.’ For Carlo, it was his deepening involvement in care ethics that challenged his religious beliefs: ‘There was...a turning point at some point when I was doing more and more care ethics and more and more studying the...care ethical approach to life’, when he ‘more and more became critical towards the Roman Catholic tradition....so you could say I said farewell to this kind of doing ethics and doing moral theology.’

Care ethics also provided Carlo with a critical lens through which to re-assess his faith: ‘I think especially the way that the Church has developed now is...no longer really helpful in bringing people closer to their Creator...and there is no feedback from empirical research to the teachings of the Church.’ Carlo maintained that the Church ‘has become a very closed world’ and ‘the more I got into care ethics, the more I got convinced that morality is not something we can put into a system and copy for centuries.’ In a similar way, Maurice expressed the belief that religious belief must be viewed under the spotlight of a care ethical perspective, arguing that ‘care is agnostic about your religious beliefs’. He explained:

‘What we want in terms of care theory is that the outcome is caring, that care is the ultimate value...Let's say you believe that God wants us all to care...that's wonderful. However, if your certainty is combined with a certain ideology or fundamentalism that divides human beings and separates them from the possibility of flourishing and their own agency in life, then I think that certainty is problematic.’

All of the examples that I’ve quoted so far have been from individuals whose religious formation was in the Christian tradition. But for me, two of the most intriguing podcast episodes, in relation to religion and spirituality, were those featuring Elissa Strauss, who is Jewish, and Sarah Munawar, a Muslim.

Sarah Munawar Elissa StraussIn Episode 13, Sarah talked about the way that stories from the Qur’an, for example the story of Yunus (Jonah), and especially the stories of women such as Hajar (Hagar) and Maryam (Mary), had provided a supportive framework for her, and her family, during her father’s protracted illness: ‘I found a lot of support in those stories because …even though we're living in very tough worlds - the world we live in today has abandoned my family in a big way - in those stories, even in the darkness of the belly of the whale, even in the desert, God's care finds you and you're cared for and your life is attended to.’ Sarah also explained the use in her writing of the term ‘the breath of Ar-Rahman’, which ‘just means...Allah is caring, compassionate, He is ever Loving...He’s a source of compassion and mercy for us’. And she added:

‘My family has been positioned in a very difficult place in this world. And the only respite and coolness and nourishment that we find is in that breath work of God's care...in our life and wherever we find it, it could be unexpected forms of care or mercy in the day....So I truly believe, and I know all Muslims believe, that part of what makes this place bearable and liveable and inhabitable is that...God gives life and that can't be taken away.’

While Sarah, like the other guests I’ve quoted, spoke about the ways in which religious faith has influenced her experience of care, by contrast Elissa Strauss spoke, in Episode 16, about the impact of caregiving, in her case as a mother, on her spiritual life. Elissa was certainly critical of the way that Judaism (in common with other major religions, in her view) has tended to idealise care in general, and motherhood in particular: ‘When mothers, particularly...are acknowledged, it's a really idealised version of motherhood...it's this kind of saintly, idealised, perfect version of what it means to care, and not the dark night of the soul piece.’ And she added: ‘While I feel like I'm in some way supported as a mom in Judaism, I don't at the same time feel like the full spiritual depth of care has been reflected to me in this tradition.’ However, Elissa also felt that her experience of caregiving as a mother had deepened her Jewish faith and practice: ‘I say I believe in God, but don't ask me to...define exactly what that means, and if I even try to, the whole thing turns to dust and falls on the ground. But I nevertheless find the relationship with this thing I call “God” but can't define as fruitful in my life.’

For Elissa, ‘one of the realest ways that care led me to a different kind of spiritual experience was my relationship with time...the miracle of [my children’s] existence, combined with the fragility of their existence, combined with the reality of time passing, brought me so much deeper into my practice as an observer of the Jewish tradition, and using Jewish tools to help order this crazy thing that is time.’ As a result, she became ‘for the first time in my life, a deeper observer of the weekly Sabbath, and I have to say that that ancient technology of the Sabbath really helps me find a deeper, richer experience of care with my kids, because I feel there's this...standing moment every week where we kind of reconnect and re-attune.’

Elissa described this as ‘just one example of the way my care experience and faith experience have been so tangled.’ She added: ‘I just want to hear so many more people talk about that, because I know it's real for many.’ I do too, which is why I’m hoping to invite more guests who are working at the intersection of faith, spirituality and care theory on to future episodes of the podcast. I’m particularly interested in exploring the question of whether adopting a care ethical perspective necessarily means abandoning an ‘orthodox’ religious position. Are care ethics and mainstream religious faith necessarily in conflict, or is it possible to imagine a creative dialogue from which both can learn? If you are doing interesting work in this area, or know of someone who is doing so, then I’d love to hear from you.

In the meantime, if the subject is of interest to you, I’d warmly recommend the 2022 collection on Care Ethics, Religion, and Spiritual Traditions, which Inge and Maurice co-edited with Maureen Sander-Staudt, and to which Inge, Maurice, Ruth, Sarah, and Steven Steyl, another of my podcast guests, as well as yours truly, contributed chapters. An open access copy of the book can be downloaded here.

Finally, I’d like to wish all those who are celebrating a Happy Christmas, or Chag Hanukkah sameach, and I hope that all of my readers and listeners enjoy a peaceful - and care-ful - holiday season.

(via spectator.co.uk)

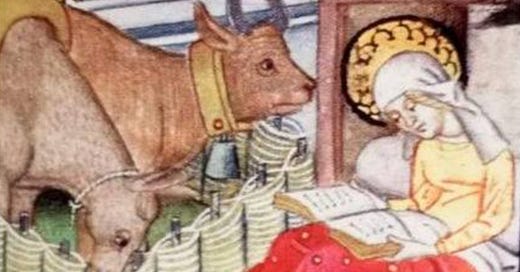

The header image for this post is from the 15th century Besançon Book of Hours, now at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, England. I love this depiction of Joseph caring for the newborn baby Jesus, enabling Mary to concentrate on her study of the Scriptures. It’s a rare example of a religious image showing a father involved in the intimate care of a child.

On this theme, I think a conversation with Sandra Sullivan-Dunbar super interesting if you can get her! Her work has been super helpful for both Elissa Strauss and myself.

At the very least you’d have two engaged listeners 😆